Before Congress, Gen. Scott Berrier, the US Defense Intelligence Agency director, acknowledged misjudging Ukraine’s ability to resist Russia: “I questioned their will to fight. That was a bad assessment.” Russia’s appraisal of Ukraine’s will to fight evidently fared no better.

Lamentably, misjudging both allies’ and adversaries’ will to fight has become routine among our military and political decision makers, with disastrous results. Social science research shows how to understand the will to fight, and to cultivate it when morally worthy. We ignore it at our peril.

Addressing Congress, Gen. Mark Milley, Chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, blamed “strategic failure” in Afghanistan on neglecting the “intangible” factor in war: “We can count the trucks and guns and the units and all that. But we can’t measure a human heart from a machine.” As President Biden put it: “We gave [Afghan forces] every tool they could need…. What we could not provide them was the will to fight.” When the Islamic State routed US-backed Iraqi forces, President Obama endorsed the judgment of his Director of National Intelligence: “We underestimated ISIL and overestimated the fighting capability of the Iraqi army… It boils down to predicting the will to fight, which is an imponderable.”

Throughout history, the most effective revolutionaries and insurgents have been “Devoted Actors” who are fused together by dedication to non-negotiable “sacred values,” like God, country, or liberty. Military incursions nearly always plan for maximum force at the beginning of to ensure victory. But if defenders resist, or are allowed to recoup, then the advantage often shifts to those with the will to fight as they increasingly harness resources against their attackers who are maxed out in terms of what they are able, or willing, to commit: consider Napoleon’s then Hitler’s onslaught against Russia, or the US invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan. In fact, just since World War II, those willing to sacrifice for cause and comrades have persisted and often prevailed against much more powerful forces that mainly rely on material incentives such as pay and punishment.

Take Ukraine today.

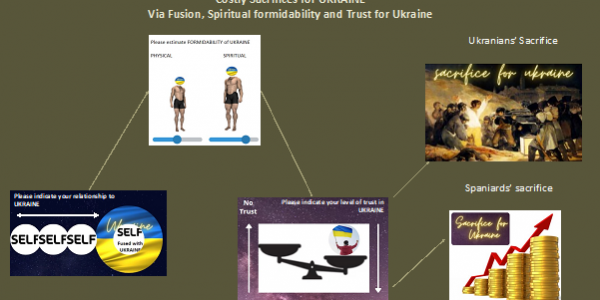

Since shortly before Russia’s invasion, we’ve conducted rolling surveys of Ukranians’ as well as Western Europeans’ willingness to sacrifice for Ukraine – as a joint effort of Artis International, Oxford University’s Changing Character of War Centre, and Spain’s Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia. Although results have yet to undergo peer review, they mirror nearly two decades of research, supported by the US Department of Defense Minerva Initiative and National Science Foundation, including battlefield studies in Iraq (with ISIS, Kurds, Arab militia, Iraqi army) and in brain and behavioral studies Asia, Africa, Europe, and with US military.

Pre- and post-invasion findings with over 1000 Ukrainians reveal that the most powerful predictor of willingness to sacrifice for Ukraine (suffer economic hardship, imprisonment, fighting, family loss, dying) is how strongly individuals “fuse” their personal identity with Ukraine. The power of that fusion is causally tied (through statistical analysis) to perceptions of Ukraine’s strong spiritual formidability and trust in Ukraine. That is, the will to fight comes from viscerally feeling one with their country and expecting it to prevail, through its spiritual authority (heartfelt inner conviction, bravery, courage).

That fusion was strong before invasion and remains strong, along with growing readiness to sacrifice for Ukraine. Our strategists would have known that, had they inquired. Since the invasion, perception of Russia’s physical and spiritual formidability have declined markedly.

The one major change, over the past horrific month, concerns eastern Ukraine (21 percent of sample, including Donbass). There, fusion with Russia diminished significantly, while fusion with Ukraine and the European Union increased – although both remain stronger in the rest of Ukraine, as does readiness to sacrifice for freedom. Even easterners, however, tend not to believe Russia will succeed (14 on a 1 to 100 scale vs. 9 for the rest of Ukraine). Across Ukraine, fusion with freedom also strongly predicts sacrifice for Ukraine when tied to fusion with democracy.

A similar general pattern arises in successive post-invasion surveys in Spain, as representative of Western European support for Ukraine, involving more than 1000 participants. The best predictor of Spaniards’ willingness to sacrifice for Ukraine is identity fusion with Ukraine, causally tied to perception of the strong spiritual formidability of Ukraine and of President Zelensky, and trust in both.

In Spain, willingness to sacrifice for Ukraine also results from identity fusion with freedom, which Zelenskyy calls the paramount “human value” at stake, and is causally tied to trust in democracy. Indeed, Spaniards express even greater willingness to sacrifice for the abstract value of freedom than for Ukraine as such.

In addressing Congress, President Zelensky stressed freedom as key to a worthy life in pursuit of happiness. This echoed what Thomas Jefferson, in his initial draft of the Declaration of Independence, deemed humankind’s “sacred rights,” absolute and non-negotiable, and for which its votaries pledged “our lives, our fortunes and our sacred honor” in battle whatever the odds. That commitment is in sharp contrast to political and military decision makers who ignore lessons from their own country’s founding by commending material over moral might in dealing with allies and adversaries in planning and executing national security and intelligence strategy.

As in deliberations on the US National Defense Strategy, the UK’s Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy calls for evidence in response to: “What are the most effective ways for the UK to build alliances and soft power?” But leveraging the moral and spiritual dimension of the will to fight is distinct from “soft power” — that is, the ability to persuade others without the threat of force or economic coercion through cultural influences, economic relationships, diplomatic tact and other means outside the realm of hard power. Will to fight is not about persuading others, but rather about harnessing inner conviction that one’s cause is right and deeply shared by those who fight alongside.

The current focus of US and NATO defense strategy concerns lessons from the Ukraine-Russia War. Our research recommends pivoting that analysis. First assess which populations have the strongest spiritual and moral force, then channel hard power to them. For Ukraine, that analysis could have yielded a strategy affording Ukraine’s defenders a greater initial material edge to accompany their spiritual and psychological strength. That same approach would not fruitlessly prolong our conflicts that lead to grievous waste of lives and treasure, as it has when funneled to groups that don’t have such spiritual and moral force (for example, Iraqi and Afghan armies) against groups that have (ISIL, Taliban). We have a chance to learn that lesson, by honoring and supporting peoples with the will to fight for the democratic freedoms that we, too, hold dear.

Scott Atran is Emeritus Research Director at France’s National Center for Scientific Research and co-founder of Artis International, and he also holds positions at Oxford University and the University of Michigan